Curanto

Stony Ground

6,000, 11,525, & 32,000 years ago…

Colonia Suiza, Rio Negra Province, Patagonia, Argentina

“You must go to a curanto,” Daniel implored. “This one in Colonia Suiza, owned by the Goye family. Many places will cook the food ahead and then bury it, pretending, but here it is authentic—the food is completely cooked in the ground. It is simple food, tasting like it is boiled. It is only on Sunday, so go tomorrow.”

A curanto is a form of cooking whereby the food, typically an assortment of five ingredients, seafood, meat, and vegetable, is placed in a pit, atop rocks first heated by a wood fire and then buried under earth. Curantos in primitive form are one of the oldest ways of cooking. The curanto of Argentina crossed over the Andes from Chile and made its way off the southern coast to the grande isle of Chiloé, where there is evidence from 6,000 years ago of such pits. Earlier finds from Polynesia and France date back even further, 11,525 and 32,000 years, respectively.

“It is easy to find, located in a gypsy village” Daniel instructed.

A gypsy village conjures the ghosts of my family, whose roots I trace to Bohemia, Poland, Lithuania, and Czechoslovakia. I see my ancestors: eyes dark, penetrating gaze, thick sinews of unruly hair black, standing defiantly, solidly on earth. An untamed blood, rebellious, free, and disdainful of authority, carries my DNA. It is no coincidence that Food whispered to me that I should find this natural and wild place—lakes of solitude, mountains cloaked in fertile green velvet moss, rivers boiling with melted glacier ice—a Bohemian camp for a pit of boulders scorched by flame, a fire-feast. I could hear the wheels of my rental car bid farewell to smooth pavement and kick up dust as the road to Colonia Suiza continued between rows of parched, dried bushes. I fretted must I wash this car before returning it? I worry if I locked the car door, the lingering anxiety of travel.

The call of free land, ley de hojar, the sitter’s land law, brought the first settlers to the edge of Lago Perito Moreno (so named after Franciso Pascasio Moreno, an Argentinian explorer, leading the incorporation of Patagonia into the Argentine nation. Perito means “specialist, expert”). The lake is filled with waters from a glacier of the same name and namesake. Colonia Suiza was founded in 1895 by Camitio and Felix Goye and Maria Felley, who immigrated to South America from their homeland of Vaud, Switzerland.

For the ten years prior to coming to Lago Perito Moreno to stake a land claim, they had lived in Chile. Then, crossing mountains, bringing with them the tradition of curanto, they remained, and from this family, Victor Goye is a descendant who perpetuates the fires of his ancestors’ cooking methods.

Colonia Suiza, located along the Circuito Chico (a 37 km loop around the lake), is no gypsy town, at least not in the sense of the place that my free-spirited ancestors would have constructed.

Once a pioneer village, it’s now a hodgepodge of craftspeople, food stalls, trinket tents, tour guides, restaurants, and antique cars and wagons—a trove for tourists. Nestled in a forest of dirt roads shaved out of the trees as if by a giant barber with an unsteady hand, the village inhabits no more than 6 - 7 hectares, roughly the area of 12 football fields. Walking is pleasant until cars and tourists arrive. I idled here for an hour as the curanto fire burned to heat the rocks in preparation. A knife maker asked about my visit, learning of my plans to visit El Calafate, the gateway to the end of the world, he extolled the virtues of Patagonian whiskey, adding that I must drink some.

El whisky debe beberse con un cubo de hielo glaciar! The whiskey must be drunk with a cube of glacier ice! He pronounced it “WEEE-ski,” chopping the last syllable abruptly, which sounded so much like the taste of bootleg liquor, that I immediately decided to adopt that pronunciation. I told him when I was further south, I would have a snort in his honor. When I made good on my long-distance toast, the resulting swig was Scotch-like, smoky, smooth fire, mellow. The restaurant in El Calafate, La Zaina, had no glacier ice.

I ambled back to Los Curantos de Victor Goye.

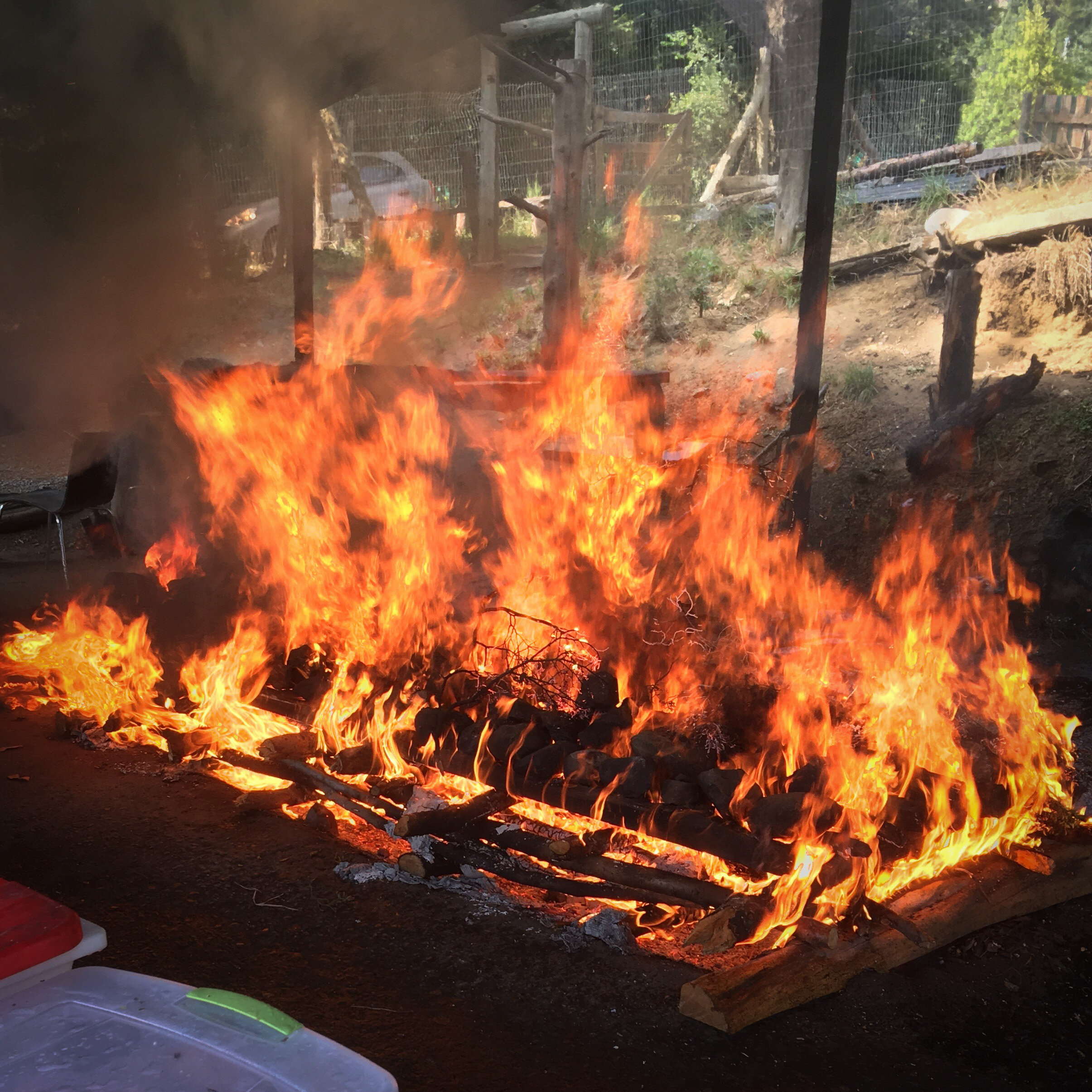

I missed the building up of the curanto. The earth was already piled up looking like a fresh grave, tended by a single man, carefully tossing a little dirt wherever a bit of steam rose as though he was preventing the escape of the food’s soul. Unlike other ways of earth-pit cooking, the curanto is built in a shallow rectangular or circular trench, not a deep one. Rounded river boulders fill the trench and a wooden blaze is set and burned on top. Once the flames have exhausted, wetted leaves are piled on the stones, then the ingredients, followed by another layer of wetted leaves, dampened burlap, and then the earth, some 7 inches deep is distributed over everything. Everything is then left to steam and cook for a few hours as a pressure cooker of sorts.

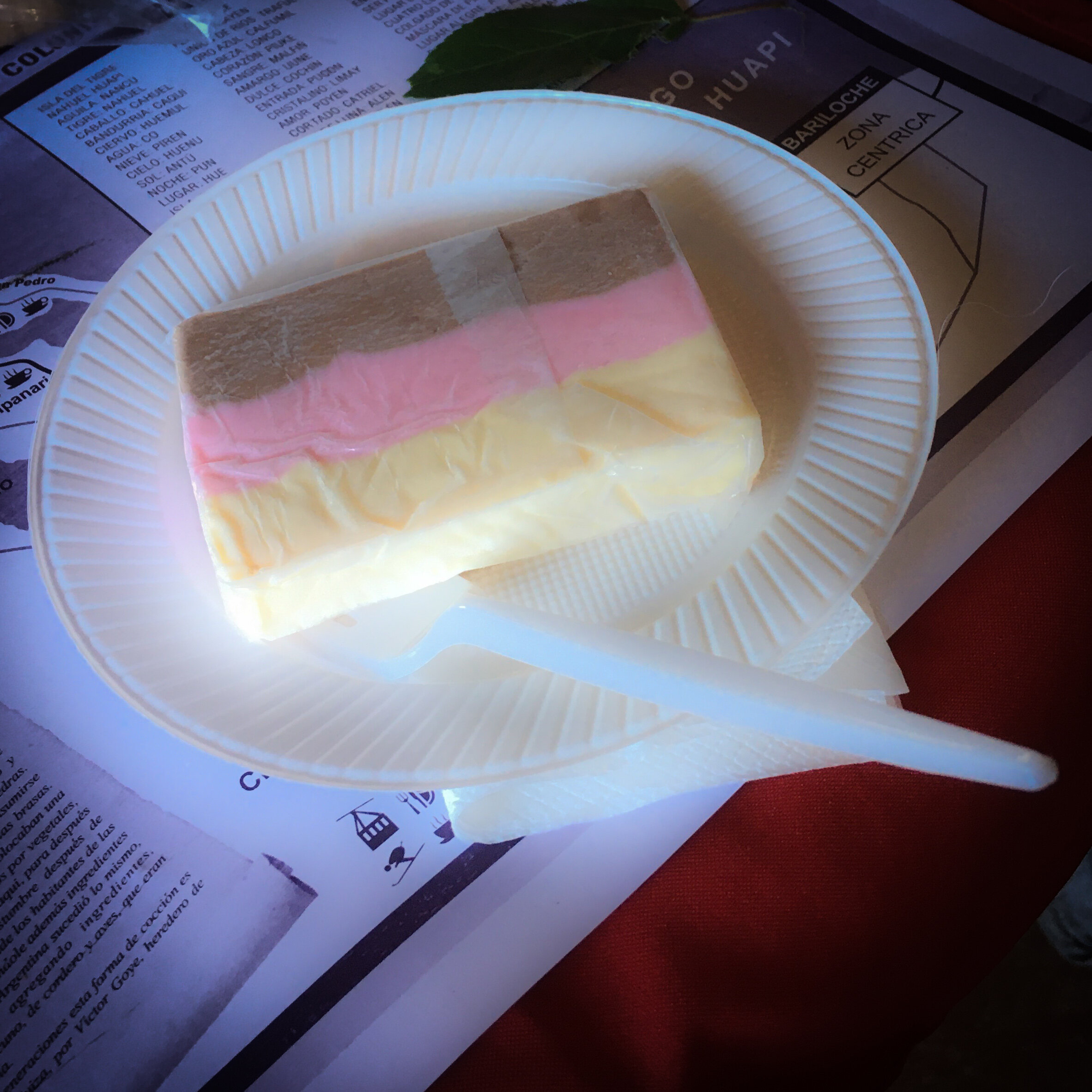

At Victor Goye’s, they cooked sausages, chicken, and beef. Vegetable complements included carrots, potatoes, apples, and winter squash stuffed with peas and corn. Often, Chilean curantos also feature tasties from the sea, including mussels and clams—precursors to a New England clam bake.

The leaves traditionally used to cover the stones and the food are called nalca or pangue; Gunnera tinctoria, a giant rhubarb look alike, though unrelated. The nalca can be used in a similar fashion as rhubarb, making jams or pies, but in the case of curanto, only for protecting the food and flavor from its steam. The plant is a native to Chile. The branches of leaves used at Victor Goye’s were definitely not the traditional nalca. Even though Daniel said they use nalca, I am trying to confirm what plant they used, believing it to be either a type of camphor tree or ficus.

At the unearthing ceremony, just prior to digging up the pit, all the guests gather round to be entertained with the curantos story recounted in song. Branches of nalca are passed around. I take the offered sprig and stick it in my hat. I do not understand most of the Spanish, but I do understand the question asked of all the attendees here to feast: ¿De dónde eres? Where are you from? I shouted out to find that I was the only one from North America in the midst of the congregation of mostly Argentinian families.

After unearthing and prior to sitting down, I was approached by a woman who had been standing behind me. Speaking English, she asked which state I lived in. My revelation that I was from North Carolina prompted her to reply, “Oh, my daughter went to school in Raleigh,” and she turned to point her out. “Did you understand the part about the leaves? He only passed them out to men. The myth of the plant is that it has aphrodisiacal powers, which is why many of the men shirked accepting it while the onlookers laughed. ” I thanked her for her kind explanation. I felt welcome.

A curanto is to be shared among family and friends, certainly not something you only do for yourself or a few people. There is too much involved to prepare; however, for a gathering, it is a simple, ancient, and satisfying way to connect with others.

The food was served in multiple waves and in complementary pairings beginning with sausage, then chicken, and finally beef, being served separately with one of the vegetables in endless amounts. Here, as in the rest of Argentina, portions are huge. Daniel was correct, the food was very simple in taste, so a dash of chimichurri was necessary to brighten flavors. I drank, of course, a malbec.

After the waves of food had crashed into all our stomachs, we were entertained with music and stories. A few people came up to me, touching my arm or shoulder, then giving me a thumbs up while saying “Estados Unidos.” I am sure that they recognized my gypsy heritage.

I drifted out, looking for the trailhead along Arroyo Goye into the Refugio Laguna Negra. I hiked the afternoon along shimmering aquamarine singing waters in summer light until dusk. As I ambled in the sunlight and gazed along the lines of tree tops, I could envision how the curanto reflected the world around it: rays of sunlight beckoned to make a home in heartwood, which accepted and accumulated the solar energy, transformed by chlorophyll into sugar and lignin, patiently waiting until the day to fall or be felled, returning sun’s heat by fire to a pit of stones. El Curanto, cooking with fire, a cycle of transformation tens of thousands of years old, a timeless magic.

Mark Rosenstein

Bariloche, Patagonia

17 February 2020