The Plague

COVID-19

The Plague

The National Emergency of COVID-19 at the Outset

The world is under quarantine.

This is a moment of disbelief. The pallor of uncertainty thickens the air we breathe. A starchy, unpalatable paste, we did not order this unsavory dish. In a matter of hours, shelves stand empty of isopropyl alcohol, Everclear, and toilet paper. Produce shelves are decimated. The madness of March is canceled. Colbert takes a hiatus. Friends stand at a distance. Communities must rise to fill in where the tide of leadership ebbs. The invisible poses danger.

Seeking guidance for understanding this day, I opened my “Zen Cookbook,” or, rather, it opened itself to me. “Chapter Five: Seeing the World Without Holding Worldly Values” in How To Cook Your Life: From Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment by Zen Master Dōgen. This book is always either on my desk or on the floor next to my bed. Dōgen addresses the issue of happiness and the assumption that everyone is seeking it. I have extensively underlined this chapter, penciled notes in the margins. One line, in particular, resonates and continues to echo: “Whatever we meet is our life.” (The emphasis is his).

I was first introduced to How To Cook Your Life by Jonathan Flaum. In the eleven years since that introduction, I have never stopped reading Dōgen or studying this work.

Flaum was the director of The WriteMind Institute for Corporate Contemplation, a writing and corporate leadership development program located in Asheville, North Carolina. I joined Flaum’s group at the end of my career at The Market Place, spurred by a continuing desire to apply the lessons of a spiritual practice to my work. Once a week, our small group would meet, beginning at 4:00 A.M. with a series of Zen practices: silent meditation, contemplative walking around the perimeter of our meditation room, and Qigong. After completing these exercises together, we cooked breakfast and served one another before beginning our required reading discussions. As soon as I encountered Dōgen, I knew that I discovered the one cookbook containing all the essential lessons for being a cook. In the monastic life of a 13th century Buddhist temple, the official carrying out the responsibilities of preparing the community’s meals has the title of tenzo. The model of tenzo now supersedes my model of chef.

Dōgen tells us to “see the four seasons of favorable circumstances, adversity, despair, and exaltation all as the scenery of your life. View the changes of the seasons as a whole, and weigh the relativeness of light and heavy from a broad perspective. …[I]t is fall...there is no need to get all upset and have a nervous breakdown...nor get all excited simply because it is spring—finding yourself in favorable circumstances.”

In the past 24 hours of coronavirus chaos, the world has flipped and with it my own sense of stability. What initially appeared to be a manageable path in financial balance suddenly shifted into unstable, shaky ground. Quickly, I clung tightly to Dōgen’s teaching, and considered that everyone around me, each of us, has the same fear, the same pain, and in this realization, I could once again feel grounded.

Where How to Cook Your Life sets the table for relating to this pandemic, Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague serves up the main course. Another of my favorite books, which I read in college and half a dozen times since, The Plague is based on a cholera epidemic in the French Algerian village of Oran.

Camus reveals a picture of society’s behaviors via the epidemic’s transformative effects on his characters. A tireless doctor, Bernard Rieux selflessly provides care and comfort even as he suffers separation from his wife and risks disease. Jean Tarrou, an accidental visitor to Oran, caught in the quarantine of the city, is moved to follow his moral compass to organize the village to fight the plague. He does so as he believes this work should not be pushed solely upon people who are compulsorily obligated to help, but that it is everyone's responsibility to lend a hand. Raymond Rambert, a journalist, considers himself beyond the quarantine, first by petitioning city bureaucracy to release him, then, upon the rejection of his application, by hiring the underworld to smuggle him out. At the moment of his attempted escape, he relents and remains, realizing the plague is everyone’s business including his.

My favorite character is the asthmatic Spaniard who, gleeful that the plague has arrived, remains in bed transferring peas back and forth between two bowls. When the gates of the city finally reopen, he puts down his peas and leaves his bed. He knows the absurdity and irrationality of the world. He recognizes how the cruel and awful indifference of the plague mirrors life itself. It is this Spaniard with whose character and insight I most identify. Life is absurd and irrational. One day the gates to the city close, and one day they will reopen. We have a choice to either remain in bed or to get up. Our lives may be as meaningless as counting peas, or they can be purposeful, but we must choose and act.

The Plague is a story of denial, false assumption, attempted suicide, opportunistic behavior, and fearless action. It is our story today. I intimately know the challenges of my restaurant friends. The plague is here, and the gates of the city have closed. Uncertainty reigns. The lifeblood of a restaurant is cash flow. It will be painful.

I have synthesized Dōgen and Camus into my practice of living—whatever I meet is my life, and the trajectory life takes is unpredictable and irrational. Both speak to a higher, underlying purpose and insist that we live, guided by a moral compass, with compassion and servitude.

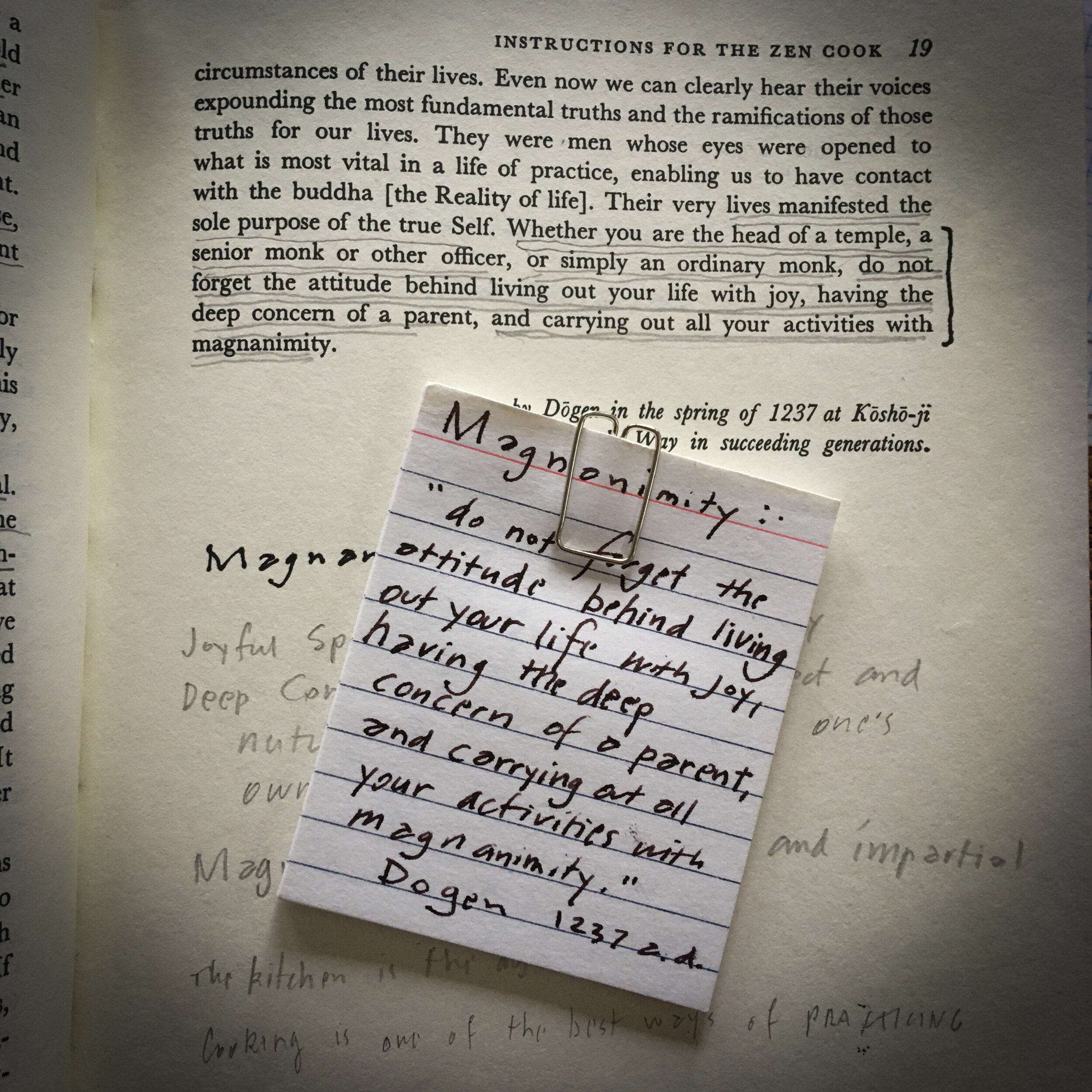

Dōgen introduces his book, which was published in 1237, with a chapter titled Instructions for the Zen Cook. In it he reveals the following to me: “Do not forget the attitude behind living your life with joy, having the deep concern of a parent, and carrying out all your activities with magnanimity.”

Magnanimity--what a delicious word! Merriam-Webster defines it as loftiness of spirit enabling one to bear trouble calmly, to disdain meanness and pettiness, and to display noble generosity. I do not use magnanimity in the Aristotelian sense, nor, do I presume, does Dōgen. Magnanimous action is the lingering aftertaste of The Plague, perhaps not in a grand way and, perhaps, not always in a joyous sense, either. It is the flavor of noble generosity. Placed on a scale that we all can understand, it is our individual humanity.

Circle of Peas - when I took this photo, I was also thinking of the asthmatic Spaniard.

The COVID-19 virus is dangerous; however, the true pandemic we face is caused by an ancient virus that we call fear. The bigger test of our individual humanity is not a financial one; the bigger test is our ability to overcome fear in order to sustain our community. If ever there was a time to consider magnanimous actions, it is today. The call for social distancing does not mean insulating ourselves from our neighbors. Do not convert the need for an air gap into a withdrawal from our responsibility to extend our (properly washed) hands outward in generosity to each other.

In the days ahead, I will take advantage of a slower pace to be in my kitchen and to cook. I will set my table and will invite you to join me. I may not sit as close as I have in times past , but I will not push away, even if my fate mirrors Rieux’s.